STRENGTH: 3,363 AAF Officers.

LOCATION: Pin point: 51º35'North latitude. 15º19'30" East longitude. Camp is situated in pine-woods area at Sagan, 168 kilometers Southeast of Berlin.

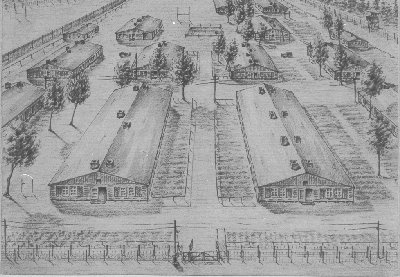

DESCRIPTION: Three of the camp's 6 compounds are occupied by Americans, 3 by RAF officers. Each compound is divided into 15 buildings or blocks housing 80 to 110 men. The 12 rooms in a block each house 2 to 10 men. Barracks are one-story, wooden hutments resembling old CCC barracks in this country. Beds are all double-deckers.

TREATMENT: An American P/W in this camp was fatally shot and another wounded under circumstances appearing to be in violation of the Geneva Convention. Fifty British POWs were murdered in March. Prior to these recent incidents, treatment had been excellent.

FOOD: Food is adequate only because of regular arrival of Red Cross food parcels, although for a time during March, 1944 POWs received only German rations insufficient for subsistence. Vegetables from individual garden plots lend variety to diet. Food parcels are pooled and men in each room take turns at cooking. One stove is available for each 100 officers. A food exchange is maintained by POWs. Cigarettes serve as the medium of exchange.

CLOTHING: Clothing is furnished by the Red Cross. Germans issue only booty and very little of that. Men need summer issue underwear.

HEALTH: Health of POWs is good. Calisthenics are compulsory by order of the Senior American Officers. Adequate medical care is provided by British and French doctors. Dental care is not satisfactory, and difficulty is experienced in obtaining glasses. Washing & toilet facilities are adequate although hot water is scarce.

RELGION: Complete religious freedom is observed. Services are held in specially constructed chapels by 9 chaplains, 7 of them Protestant, 2 Catholic. One chaplain is Lt. Eugene L. Daniel, an American; the others are British.

MAIL: Airmail from camp averages 1½ months in transit, surface mail 3 months. Next-of-kin and tobacco parcels average 2½ months travel time. Sometimes they are pilfered.

RECREATION: This camp has the best organized recreational program of the American camps in Germany. Each compound has an athletic field and volleyball courts. The men participate in basketball, softball, boxing, touch football, volleyball, table tennis, fencing. Leagues have been formed in most of these sports. A fire pool 20' x 22' x 5' is occasionally used for swimming. Parole walks are sometimes permitted. In each of the compound theaters built by the POWs, plays and musical comedies are frequently presented. Top-flight swing bands and orchestras perform regularly, and several choral groups take part in religious services and camp entertainment. Other recreational activities include bridge tournaments, building of model planes, visits to occasional movies, listening to phonograph recordings. Competent instructors teach a wide range of cultural and technical subjects, and lectures and discussions are numerous. A newspaper posted 4 times weekly is edited by the POWs. Each of the compounds has a well-stocked library.

WORK: Officers are not required to work. However, a small tin-shop is staffed by POWs who voluntarily make plates and cooking pans from biscuit and other tins, while a broom shop produces brooms largely from Red Cross wrapping cord.

PAY: Men are paid on a sliding scale according to rank. Lts. receive 81 marks monthly in lagergeld of which 40 are deducted for food and orderly services. The remainder may be used at the canteen which has weak beer 4 times a year and a meager supply of harmonicas, pottery, and gadgets.

LOCATION: Until 27 Jan. 1945, Stalag Luft 3 was situated in the Province of Silesia, 90 miles southeast of Berlin, in a stand of fir trees south of Sagan (51º35'N latitude, 15º19'30" E longitude).

In the Jan. exodus, the South Compound & Center Compound moved to Stalag 7A, Moosburg (48º27' North latitude - 11º57' East longitude). The West Compound & North Compound moved to Stalag 13D, Nurnerg-Langwasser (49º27' N latitude, 11º50' E longitude) and then proceeded to Moosburg, arriving 20 April 1945.

STRENGTH: On 14 April 1942 Lt. (j.g.) John E. Dunn, 0-6545, U.S. Navy, was shot down by the Germans and subsequently became the 1st American flyer to be confined in Stalag Luft 3, then solely a prison camp for officers POWs of the Royal Air Force. By 15 June 1944, U.S. Air Force officers in camp numbered 3,242, and at the time of the evacuation in Jan. 1945, the International Red Cross listed the American strength as 6,844. This was the largest American officers' camp in Germany.

DESCRIPTION: When the first Americans arrived in 1942, the camp consisted of 2 compounds or enclosures, one for RAF officers and one for RAF NCOs. The rapid increase in strength forced the Germans to build 4 more compounds, with USAAF personnel taking over the Center, South, West and sharing the North Compound with the British. Adjoining each compound the Germans constructed other enclosures called "vorlagers" in which most of the camp business was transacted and which held such offices as supply, administration and laundry.

Each compound enclosed 15 one-story, wooden barracks or "blocks". These, in turn, were divided into 15 rooms ranging in size from 24' x 15' to 14' x 6'. Occupants slept in double-decker bunks and for every 3 or 4 men the Germans provided simple wooden tables, benches & stools. One room, equipped with a cooking range, served as a kitchen. Another, with 6 porcelain basins, was the washroom. A third, with 1 urinal & 2 commodes, was the latrine.

A block could house 82 men comfortable, but with the growth in numbers of POWs, rooms assigned for 8 men began holding 10 and then 12, and the middle of Sept. 1944 saw new POWs moving into tents outside the barracks.

Two barbed wire fences 10' high and 5' apart surrounded each compound. In between them lay tangled barbed wire concertinas. Paralleling the barbed wire and 25' inside the fence ran a "warning wire" strung on 30" wooden posts. The zone between the warning wire and the fence was forbidden territory, entrance to which was punishable by sudden death. At the corners of the compound and at 50-yard intervals around its perimeter rose 40' wooden guard towers holding Germans armed with rifles or machine guns.

U.S. PERSONNEL: Lt. Col. Albert P. Clark, Jr., captured on 26 July 1942, became the first Senior American Officer, a position he held until the arrival of Col. Charles G. Goodrich some 2 months later. The enforced seclusion of individual compounds necessitated the organization of each as an independent POWs camp. At the time of the move from Sagan, camp leaders were as follows:

| Senior Allied Officer: | Brigadier General Arthur W. Vanaman | |

| SAO South Compound: | Col. Charles G. Goodrich | |

| SAO Center Compound: | Col. Delmar T. Spivey | |

| SAO West Compound: | Col. Darr H. Alkire | |

| North Compound: | Lt. Col. Edwin A. Bland |

The staff of a compound was organized into two categories:

| Main Staff Departments | Secondary Staff Departments | |

| a. Adjutant | a. Mail | |

| b. German property | b. Medical | |

| c. German rations | c. Coal | |

| d. Red Cross food | d. Finance | |

| e. Red Cross clothing | e. Canteen |

The basic unit for organization was the barrack building or block. Block staffs were organized to include the same functions as the Compound Staff, and the blocks themselves were sub-divided into squads of 10 men each.

Each compound had a highly organized Security Committee.

GERMAN PERSONNEL: The original commandant of Stalag Luft 3 was Oberst von Lindeiner, an old-school aristocrat with some 40 years of army service. Courteous and considerate at first sight, he was inclined to fits of uncontrolled rage. Upon one occasion he personally threatened a POWs with a pistol. He was, however, more receptive to POWs requests than any other commandant.

After the British mass escape of March 1944, Oberst von Lindeiner was replaced by Oberstleutnant Cordes, who had been a POW in World War I. A short while later Cordes was succeeded by Oberst Braune, direct & business-like. Stricter than his predecessors, he displayed less sympathy toward POWs requests. Nevertheless, he was able to stop misunder- standings such as the one resulting in guards shooting into the compounds. In general, commandants tended to temporize when dealing with POWs, or else to avoid granting their requests entirely.

Most disliked by POWs were the Abwehr or Security officers - Hauptmann Breuli and his successor Major Kircher.

The Luftwaffe guards were 4th rate troops either peasants too old for combat duty or young men convalescing after long tours of duty or wounds received at the front. They had almost no contact with POWs. In addition to uniformed sentries, soldiers in fatigues were employed by the Germans to scout the interiors of the compounds. These "ferrets" hid under barracks, listened to conversations, looked for tunnels and made themselves generally obnoxious to the POWs. The German complement totaled 800.

Occasionally, as after the March 1944 mass escape, Gestapo groups descended upon the camp for a long, thorough search.

TREATMENT: Because of their status as officers and the fact that their guards were Luftwaffe personnel, the men at Stalag Luft 3 were accorded treatment better than that granted other POWs in Germany. Generally, their captors were correct in their adherence to many of the tenets of the Geneva Convention. Friction between captor & captive was constant and inevitable, nevertheless, and the strife is well illustrated by the following example.

On 27 March 1944 the Germans instituted an extra appel (roll call) to occur any time between the regular morning and evening formations. Annoyed by an indignity which they considered unnecessary, POWs fought the measure with a passive resistance. They milled about, smoked, failed to stand at attention and made it impossible for the lager officer to take a count. Soon they were dismissed. Later in the day another appel was called. This time the area was lined with German soldiers holding rifles and machine guns in readiness to fire. Discreetly, POWs allowed the appel to proceed in an orderly fashion. A few days later, nevertheless, probably as a result of this deliberate protest against German policy, the unwonted extra appel was discontinued.

Since the murder of 50 RAF flyers has been attributed to the Gestapo, acts of atrocious mistreatment involving the regular Stalag Luft 3 guard complement may be narrowed down to two.

About 2200 hours, 29 Dec. 1943, a guard fired a number of shots into one barrack without excuse or apparent purpose. One bullet passed through the window and seriously wounded the left leg of Lt. Col. John D. Stevenson. Although Col. Stevenson spent the next 6 months in hospitals, the wound has left him somewhat crippled.

About 1230 hours, 9 April 1944, during an air raid by American bombers, Cpl. Cline C. Miles was standing in the cookhouse doorway. He was facing the interior. Without warning a guard fired at "a man" standing in the doorway. The bullet entered the right shoulder of Cpl. Miles and came out through his mouth killing him instantly.

FOOD: German rations, instead of being the equivalent of those furnished depot troops, compared with those received by non-working civilians - the lowest in Germany. While insufficient, these foods provided the bulk of staples, mainly through bread and potatoes. A PW's average daily issue of foods, with caloric content included, follows:

The staff of a compound was organized into two categories:

| TYPE OF FOOD | GRAMS | CALORIES | |

| Potatoes | 390 | 331 | |

| Bread | 350 | 910 | |

| Meat | 11 | 20 | |

| Barley, Oats, Etc | 21 | 78 | |

| Kohlrabi | 24 | 87 | |

| Dried vegetable | 14 | 38 | |

| Margarine | 31 | 268 | |

| Cheese | 10 | 27 | |

| Jam | 25 | 69 | |

| Sugar | 25 | 100 | |

| ------------- | ------------- | ------------- | |

| TOTALS | 1124 | 1928 |

A conservative estimate of the caloric requirement of a person sleeping 9 hours a day and taking very little exercise is 2,150 calories. German rations, therefore, fell below the minimum requirement for healthy nutrition.

Food came from 4 other sources: Red Cross parcels, private parcels, occasional canteen purchases and gardens. Of the Red Cross parcels, after the spring of 1943, 40% were American, 25% British, 25% Canadian and 10% miscellaneous such as New Zealand parcels, Christmas parcels and bulk issue from the British colony in Argentina. These were apportioned at the rate of 1 per man per week during periods of normal supply. If the International Red Cross at Geneva felt that transportation difficulties would prevent the usual delivery, it would notify the camp parcel officer to limit the issue to parcel per man per week. Such a situation arose in Sept. 1944 when all Stalag Luft 3 went on ½ parcels. Average contents of American & British parcels were as follows:

| PERSONNEL | South Compound: | American Sr. Officer: | Col. Charles G. Goodrich |

| Center Compound: | American Sr. Officer: | Col. Delmar Spivey | |

| West Compound: | American Sr. Officer: | Col. Darr H. Alkire | |

| German Commandant: | Oberst von Lindeiner |

Since the kitchen equipment of 10 boilers and 2 ovens per compound was obviously inadequate, almost all food was prepared by the various room messes in the blocks. These messes obtained from the kitchen only hot water and, four times a week, hot soup. Cooking within the block was performed on a range whose heating surface was 3 square feet. During winter months, POWs were able to use the heating stoves in their rooms as well. With few exceptions, each room messed by itself. All food was pooled, and room cooks were responsible for serving it in digestible and appetizing, if possible, form. Since the stove schedule provided for cooking periods from 3 p.m. to 9 p.m., some rooms ate their main meal in mid-afternoon, while others dined fashionably late. Below is a typical day's menu:

Breakfast - 9 a.m. Two slices of German bread with spread, coffee (soluble) or tea. Lunch - noon Soup (on alternate days), slice of German bread, coffee or tea.

Supper - 5:30 p.m. Potatoes, one-third can of meat, vegetables (twice a week), slice German bread, coffee or tea. Evening snack - 10 p.m. Dessert (pie, cake, etc) coffee or cocoa.

A unique POWs establishment was Foodacco whose chief function was to provide POWs with a means of exchange and a stable barter market where, for example, cocoa could be swapped for cigars. Profits arising from a 2% commission charged on all transactions was credited to a communal camp fund.

HEALTH: Despite confinement, crowding, lake of medical supplies and poor sanitary facilities, health of POWs was astonishingly good.

For trivial ailments, the compounds maintained a first aid room. More serious cases were sent to 1 of the 2 sick quarters within the camp. Sick quarters for the South Compound originally consisted of a small building with 24 beds, a staff of 3 PW doctors and some PW orderlies. This also served the North & West Compounds. The Center Compound had its own dispensary and 2 PW doctors. On 1 June 1944, the three-compound sick quarters was replaced by a new building with 60 beds.

The Germans furnished very few medical supplies. As a result, POWs depended almost wholly on the Red Cross. Large shipments of supplies, including much-needed sulfa drugs, began to arrive in the autumn of 1944. POWs were also glad to receive a small fluoroscope and thermometers.

Most common of the minor illnesses were colds, sore throats, influenza, food poisoning and skin diseases. When a PW needed an x-ray or the attentions of a specialist, he was examined by a German doctor. It usually took months to obtain these special attentions. Cases requiring surgery were sent to one of the English hospitals, as a rule Lamsdorf or Obermassfeld. Emergency cases went to a French hospital at Stalag 8C, one mile distant.

Dental care for the North, West & South Compounds was provided by a British dentist and an American dental student. In 14 months, they gave 1,400 treatments to 308 PW from the South Compound alone.

Sanitation was poor. Although POWs received a quick delousing upon entry into the camp, they were plagued by bedbugs and other parasites. Since there was no plumbing, both indoor and outdoor latrines added to the sanitation problem in summer. POWs successfully fought flies by scrubbing aborts daily, constructing fly traps and screening latrines with ersatz burlap in lieu of wire mesh.

Bathing facilities were extremely limited. In theory the German shower houses could provide each man with a three- minute hot shower weekly. In fact, however, conditions varied from compound to compound and if a PW missed the opportunity to take a hot shower he resorted to a sponge bath with water he had heated himself - the only other hot water available the year around.

CLOTHING: In 1943, Germany still issued booty clothing of French, Belgian or English derivation to POWs. This practice soon ceased, making both Britons & Americans completely dependent on clothing received from the Red Cross. An exception to the rule was made in the winter of 1943 when the camp authorities obtained 400 old French overcoats from Anglo-American POWs.

Gradually, Americans were able to replace their RAF type uniforms with GI enlisted men's uniforms, which proved extremely serviceable. When stock of clothing permitted, each PW was maintained with the following wardrobe:

WORK: Officers were never required to work. To ease the situation in camp, however, they assumed many housekeeping chores such as shoe repairing, distributing food, scrubbing their own rooms and performing general repair work on barracks.

Other chores were carried out by a group of 100 American orderlies whose work was cut to a minimum and whose existence officers tried to make as comfortable as possible under the circumstances.

PAY: The monthly pay scale of officers in Germany was as follows:

Americans adhered closely to the financial policy originated by the British in 1940-42. No money was handled by individual officers but was placed by the accounts officer into individual accounts of each after a sufficient deduction had been made to meet the financial needs of the camp. These deductions, not to exceed 50% of any officer's pay, took care of laundry, letter forms, airmail postage, entertainment, escape damages and funds transmitted monthly to the NCO camps, which received no pay until July 1944.

Officers at Stalag Luft 1 contributed 33% of their pay to the communal fund, and the entire policy was approved by the War Department on 14 Oct. 1943. Since the British Government unlike the U.S.A. deducted PW pay from army pay, Americans volunteered to carry out all canteen purchases with their own funds, but to maintain joint British-American distribution just as before.

Because of the sudden evacuation from Sagan, Allied POWs had no time to meet with German finance authorities and reconcile outstanding Reichsmark balances. The amount due to the U.S.A. alone from the German Government totals 2,984,932.75 Reichsmarks.

MAIL: Mail from home or sweetheart was the life-blood of PW. Incoming mail was normally received 6 days a week, without limit as to number of letters or number of sheets per letter. (German objected only to V-mail forms.) Incoming letters could travel postage free, but those clipper-posted made record time. Correspondence could be carried on with private persons in any country outside of Germany; Allied, neutral or enemy. Within Germany correspondence with next- of-kin only was permitted. A PW could write one letter per month to next-of-kin in another PW camp or internees' camp.

SOUTH COMPOUND INCOMING MAIL

| MONTH | LETTERS | PER CAPITA | AGE |

| Sep. 43 | 3,190 | 3 | 11 weeks |

| Oct. 43 | 5,392 | 5 | 10 weeks |

| Nov. 43 | 9,125 | 9 | 10 weeks |

| Dec. 43 | 24,076 | 24 | 8 weeks |

| Jan. 44 | 7,680 | 7 | 12 weeks |

| Feb. 44/td> | 10,765 | 9 | 12 weeks |

| Mar. 44 | 11,693 | 10 | 12 weeks |

| Apr. 44 | 16,355 | 15 | 12 weeks |

| May 44 | 15,162 | 13 | 13 weeks |

| Jun. 44 | 13,558 | 11 | 14 weeks |

| Jul. 44 | 24,440 | 20 | 14 weeks |

| Aug. 44 | 14,264 | 11 | 15 weeks |

| Sep. 44 | 10,277 | 8 | 16 weeks |

The travel time reverted to 11-12 weeks in the autumn of 1944, with airmail letters sometimes reaching camp in 4 to 6 weeks. All mail to Luftwaffe-held POWs was censored in Sagan by a staff of German civilian men and women. Outgoing mail was limited, except for special correspondence, to 3 letter forms and 4 cards per PW per month. Officers above the rank of major drew 6 letters and 4 cards while enlisted men received 2 letter forms and 4 cards. Protected personnel received double allotments. POWs paid for these correspondence forms and for airmail postage as well.

SOUTH COMPOUND OUTGOING MAIL

| MONTH | LETTERS | POSTAGE |

| Sep. 43 | 3,852 | 924.60 |

| Oct. 43 | 6,711 | 2494.60 |

| Nov. 43 | 7,781 | 2866.66 |

| Dec. 43 | 7,868 | 2968.00 |

| Jan. 44 | 7,811 | 2915.30 |

| Feb. 44/td> | 7,958 | 2907.10 |

| Mar. 44 | 7,916 | 3095.80 |

| Apr. 44 | 8,460 | 3154.90 |

| May 44 | 8,327 | 3050.20 |

| Jun. 44 | 10,189 | 3789.60 |

| Aug. 44 | 8,780 | 3366.50 |

| Sep. 44 | 8,777 | 3288.30 |

Each 60 days, a PW's next-of-kin could mail him a private parcel containing clothing, food and other items not forbidden by German or U.S. Government regulations. These parcels too, were thoroughly examined by German censors.

MORALE: Morale was exceptionally high. POWs never allowed themselves to doubt an eventual Allied victory and their spirits seared at news of the European invasion. Cases of demoralization were individual, caused for the most part by reports of infidelities among wives or sweethearts, or lack of mail, or letters in which people failed completely to comprehend PW's predicament. Compound officers succeeded in keeping their charges busy either physically or mentally and in maintaining discipline. The continual arrival of new PW with news of home and the air force also helped to cheer older inmates.

WELFARE: The value of the Protecting Power in enforcing the provisions of the Geneva Convention lay principally in the pressure they were able to bring to bear. Although they: might have agreed with the POWs point of view, they had no means of enforcing their demands upon the Germans, who followed the Geneva Convention only insofar as its provisions coincided with their policies. But the mere existence of a Protecting Power, a third party, had its beneficial effect on German policy.

Direct interview was the only satisfactory traffic with the Protecting Power. Letters usually required 6 months for answer - if any answer was received. The sequence of events at a routine visit of Protecting Power representatives was as follows: Granting by the Germans of a few concessions just prior to the visit; excuses given by the Germans to the representatives; conference of representatives with compound seniors; conference of representative with Germans. Practical benefits usually amounted to minor concessions from the Germans.

POWs of Stalag Luft 3 feel a deep debt of gratitude toward the Red Cross for supplying them with food and clothing, which they considered the 2 most important things in their PW camp life. Their only complaint is against the Red Cross PW Bulletin for its description of Stalag Luft 3 in terms more appropriately used in depicting life on a college campus than a prison camp.

POWs also praised the YMCA for providing them generously with athletic equipment, libraries, public address systems and theatrical materials. With YMCA headquarters established in Sagan, the representative paid many visits to camp.

RELIGION: On I Dec. 1942, the Germans captured Capt. M.E. McDonald with a British Airborne Division in Africa. because he was "out of the cloth" they did not officially recognize him as a clergyman, nevertheless, he was the accredited chaplain for the camp and conducted services for a large Protestant congregation. He received a quantity of religious literature from the YMCA and friends in Scotland. In April 1942, Father Philip Goudrea, Order of Mary Immaculate, Quebec, Canada, became the Catholic Chaplain to a group which eventually numbered more than 1,000 POWs. Prayer books were received from Geneva and rosary beads from France.

On 12 Sept. 1943, a Christian Science Group was brought together in the South compound under the direction of 2nd Lt. Rudolph K. Grurmm, 0-749387. His reading material was forwarded by the Church's War Relief Committee, Geneva, as was that of 1st Lt. Robert R. Brunn active in the Center Compound. Thirteen members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, sometimes known as the Mormon Church, held their first meeting in the South Compound on 7 Nov. 1943. 1st Lt. William E. McKell was nominated as presiding Elder and officiated at subsequent weekly meetings. Material was supplied by the European Student Relief Fund, the Red Cross, the YMCA and the Swiss Mission of the Church.

RECREATION: Reading was the greatest single activity of POWs. The fiction lending library of each compound was enlarged by books received from the YMCA and next-of-kin until it totaled more than 2,000 volumes. Similarly, the compounds' reference libraries grew to include over 500 works of a technical nature. These books came from the European Student Relief Fund of the YMCA and from POWs who had received them from home.

Athletics were second only to reading as the most popular diversion. Camp areas were cleared and made fit playing fields at first for cricket and rugby and later for softball, touch football, badminton, deck tennis and volleyball. In addition, POWs took advantage of opportunities for ping pong, wrestling, weight lifting, horizontal and parallel bar work, hockey and swimming in the fire pool. The bulk of athletic equipment was supplied by the YMCA.

The "Luftbandsters", playing on YMCA instruments, could hold its own with any name band in the U.S.A. according to those who heard them give various performances. POWs formed junior bands of less experienced players and also a glee club.

Through the services of the YMCA, POWs were shown 7 films, 5 somewhat dated Hollywood features and 2 German musical comedies.

Other activities included card playing, broadcasting music and news over a camp amplifier called "Station KRGY", reading the "Circuit" and "Kriegie Times" journals issued by POWs news room, attending the Education Department's classes which ranged from Aeronautics to Law, painting, sketching and the inevitable stroll around the compound perimeter track.

SAGAN EVACUATION: At 2100 hours on 27 Jan. 1945, the various compounds received German orders to move out afoot within 30 minutes. With an eye on the advancing Red Armies, POWs had been preparing two weeks for such a move. Thus the order came as no surprise. In barracks bags, in knotted trousers and on makeshift sleds they packed a minimum of clothing and a maximum of food - usually one parcel per man. Each man abandoned such items as books, letters, camp records and took his overcoat and one blanket. Between 2130 & 2400 hours, all men, except some 200 too weak to walk, marched out into the bitter cold and snow in a column of threes - destination unknown. Their guards, drawn from the camp complement, bore rifles and machine pistols. They marched all night, taking 10 minute breaks every hour.

The exodus was harrowing to POWs of all compounds but especially those of the South, which made the 55 kilometers from Sagan to Muskau in 27 hours with only 4 hours of sleep. Rations consisted only of bread and margarine obtained from a horse-drawn wagon. POWs slept in unheated barns. At Muskau, on the verge of exhaustion, they were billeted in a blast furnace, which was warm and an empty heating plant, which was cold. Here they were given a 30-hour delay for recuperation. Even so, some 60 men incapable of marching farther had to be left behind. The 25 kilometers from Muskau to Spremberg on 31 Jan., the South compound, plus 200 men from the West compound, went to Stalag 7A at Moosburg. They traveled 2 days and 2 nights in locked, unmarked freight cars - 50 men to a car. On 7 Feb., the Center Compound joined them. The North Compound fell in with the West Compound at Spremberg and on 2 Feb. entrained for Stalag 13D, Nurnberg, which they reached after a trip of 2 days.

Throughout the march the guards, who drew rations identical with POWs, treated their charges with sympathy and complained at the harshness they all had to undergo. German civilians encountered during the trek were generally considerate, bartering with PW and sometimes supplying them with water.

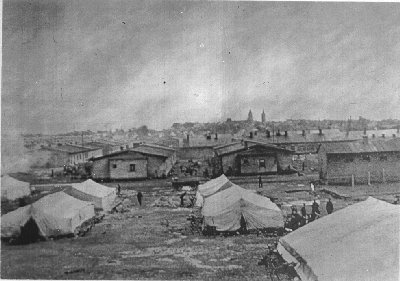

STALAG 13D CONDITIONS: Conditions at Stalag 13D, where POWs stayed for 2 months, were deplorable. The barracks originally built to house delegates to the Nazi party gatherings at the shrine city, had recently been inhabited by Italian POWs, who left them filthy. There was no room to exercise, no supplies, nothing to eat out of and practically nothing to eat inasmuch as no Red Cross food parcels were available upon the Americans' arrival. The German ration consisted of 300 grams of bread, 250 grams of potatoes, some dehydrated vegetables and a little margarine. After the first week, sugar was not to be had and soon the margarine supply was exhausted. After 3 weeks, and in answer to an urgent request, 4,000 Red Cross food parcels arrived from Dulag Luft, Wetzlar. Shortly thereafter, the Swiss came to make arrangements for sending parcels in American convoy, and soon Red Cross parcels began to arrive in GI (Red Cross) trucks.

Throughout this period, large numbers of American POWs were pouring into camp - 1,700 Stalag Luft 4, 150 a day from Dulag Luft and finally some men from Oflag 64.

Sanitation was lamentable. The camp was infested with lice, fleas and bedbugs. 3,000 men each with only 2 filthy German blankets, slept on the bare floors. Toilet facilities during the day were satisfactory, but the only night latrine was a can in each sleeping room. Since many men were afflicted with diarrhea, the can had an insufficient capacity and men perforced soiled the floor. Showers were available once every 2 weeks. Barracks were not heated. Only 200 kilograms of coal were provided for cooking. Morale dropped to its lowest ebb, but Col. Darr H. Alkire succeeded in maintaining discipline.

NURNBERG EVACUATION: At 1700 hours on 3 April 1945, the Americans received notice that they were to evacuate the Nurnberg camp and march to Stalag 7A, Moosburg. At this point, the POWs took over the organization of the march. They submitted to the German commander plans stipulating that in return for preserving order they were to have full control of the column and to march no more than 20 kilometers a day. The Germans accepted. On 4 April, with each PW in pos- session of a food parcel, 10,000 Allied POWs began the march. While the column was passing a freight marshalling yard near the highway, some P-47s dive-bombed the yard. Two Americans and one Briton were killed and 3 men seriously wounded. On the following day the column laid out a large replica of an American Air Corps insignia on the road with an arrow pointing in the direction of the march. Thereafter, the column was never strafed. It proceeded to Neumarkt, to Bersheim where 4,500 Red Cross parcels were delivered by truck, then to Mulhauser where more parcels were delivered. On 9 April, the compound column reached the Danube which Col. Alkire flatly refused to cross since it meant exceeding the 20 kilometer-a-day limit. With his refusal the Germans completely lost control of the march and POWs began to drop out of the column almost at will. The guards, intimidated by the rapid advance of the American Army, made no serious attempt to stop the disintegration. The main body of the column reached Stalag 7A on 20 April 1945.

"SOURCE MATERIAL FOR THIS REPORT CONSISTED OF INTERROGATIONS OF FORMER PRISONERS OF WAR MADE BY CPM BRANCH, MILITARY INTELLIGENCE SERVICE, AND REPORTS OF THE PROTECTING POWER AND INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS RECEIVED BY THE STATE DEPARTMENT (Special War Problems Division)." Taken from the introduction (general) of camps.

This material brings together the efforts of many organizations and individuals with an interest in preserving the remarkable experiences of those who faced combat in the skies of Europe during World War II and who suffered incarceration in Germany's World War II prisoner of war camps. The materials in this section reside in the U.S. Air Force Academy Library's Special Collections and are on occasional display in the Academy's Cadet Library. The Academy Library is especially grateful to The Friends of the Academy Library for their untiring efforts supporting its work.

The researchers of this web site material wish to acknowledge the extensive support received from Duane Reed, Chief of the Special Collections Branch.

Statistics published after the war by the Army Air Forces tell a dramatic story about the air war against Germany. During the course of the war, 1,693,565 sorties were flown -- a sortie defined as one aircraft airborne on a mission against the enemy. Of these missions, 89% were deemed effective. Mission accomplished! Flying these missions were 32,263 combat aircraft. Fifty-five percent of these planes were lost in action. On the other hand 29,916 enemy aircraft were destroyed. On the human side, there were 94,565 American air combat casualties. Killed in action accounted for 30,099, with 13,660 wounded and evacuated. The remaining 51,106 were missing in action, POWs, evaders, and internees. Miracles of survival were numerous. Stalag Luft III held many fliers whose planes exploded in the air -- disintegrated -- yet one, two or more crew members survived. Some were blasted unconscious into the sky, and came to on the ground, their open parachutes beside them. Others were literally dug out of the wreckage of their crashed airplanes -- horribly injured, yet survivors.

There were countless instances of men surviving the catastrophic destruction of their aircraft high in the sky. The accounts of explosion and fire which left men unconscious in the air only to have them land safely by parachute were so common that in Stalag Luft III such survivors had difficulty finding an audience for the story.

In the last year of the war the German leadership actually encouraged enraged civilians, who had captured Allied airmen who were destroying their cities and killing their women and children, to wreak their vengeance on them indiscriminately. How many men died this way is known only to God. Fortunately, and to their credit, German military personnel aggressively defended shot-down airmen from such outrages.

Dulag Luft, located near Frankfurt am Main, was the Luftwaffe Aircrew Interrogation Center to which all Allied airmen were delivered as soon as possible after their capture. There each new prisoner, while still trying to recover from the recent trauma of his shoot-down and capture, was skillfully interrogated for military information of value to the Germans. The German interrogators claimed that they regularly obtained the names of unit commanders, information on new tactics and new weapons, and order of battle from naive or careless U.S. airmen, without resort to torture. New prisoners were kept in solitary confinement while under interrogation and then moved into a collecting camp. After a week or ten days, they were sent in groups to a permanent camp such as Stalag Luft III for officers or Stalag VIB for enlisted men. A nearby hospital employing captured doctors and medical corpsmen received and cared for wounded prisoners.

Stalag Luft III was located 100 miles southeast of Berlin in what is now Poland. The POW camp was one of six operated by the Luftwaffe for downed British and American airmen. Compared to other prisoner of war camps throughout the Axis world, it was a model of civilized internment. The Geneva Convention of 1929 on the treatment of prisoners of war was complied with as much as possible, but it was still war, still prison, and still grim. With a madman on top, there was the ever-present threat that authority above the Luftwaffe could change things on a whim. Kriegies always knew that they were living on the razor's edge.

The officer airmen who were POWs in the German camps at Stalag Luft III arrived there through an accident of war. They varied widely in age, military rank, education, and family background, but had several common experiences:

This unique selection process seemed to give these men some common characteristics. They had an uncommon love of country and a loyalty to each other. They were very resourceful and applied great skill to improve their living conditions and to conduct escape and other clandestine activities. They indeed became a band of brothers.

In retrospect, most later acknowledged that their experience as prisoners was not simply an unpleasant waste of time but that they came out of it with, among other things, a clearer sense of values, a strengthened love of country, improved leadership skills, and an improved ability to live in harmony with others under difficult circumstances.

After the war the majority continued their comradery by staging many heart-warming reunions and by establishing at the Air Force Academy Library a central location for the preservation of their memorabilia and the records of their incarceration. Many went on to complete successful and distinguished careers in the Air Force, or in civilian life, some as political appointees in government, others in the professions, including the ministry.

The German garrison of Stalag Luft III was composed of non-flying Luftwaffe officers and enlisted personnel who were generally not qualified for frontline duty. Many of the guards were old and uneducated. Some had been wounded in combat and wore the patches of famous battles on the Eastern Front against Russia. For the enlisted men, guarding prisoners was probably regarded as better than duty in the East, but for the officers it must have been one of the least desired assignments. Some officers and men of the camp's garrison were genuinely hated by the prisoners. Most of the others tried to be decent to the POWs, often under difficult circumstances and the threat of severe punishment if they were caught doing anything that could be considered contrary to Germany's war effort. This general feeling of mutual respect is reflected in the fact that Gustav Simoleit and Hermann Glemnitz were invited as guests to the 20-year reunion of the American Former Prisoners of Stalag Luft III. They were warmly received.

Food was always very close to a prisoner's heart. Germany, involved in a total war, had difficulties enough feeding its own people. Feeding POWs was well down on the list of priorities. The German POW rations were insufficient to sustain health and failed to meet the requirements of the Geneva Convention. Had the International Red Cross not shipped food parcels to all Allied POW camps except to the Russians, serious malnutrition would have been common. The Red Cross offer to feed the Russian POWs was spurned by Stalin. The receipt of the Red Cross food parcels suffered from the uncertainties of the wartime rail service in Germany and the caprice of the Germans who would withhold delivery of the food as group punishment.

Kriegies stashed food for special occasions. A few spoons of British cocoa here or a few lumps of sugar there all went into a special reserve for what the Kriegies called a bash. Loosely speaking a bash was the Kriegies' way of celebrating a special event, perhaps the Fourth of July, Christmas, or even a birthday. Its ingredients had been saved laboriously for months. It was a feast.

The International Young Men's Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.). with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, undertook to preserve the quality of life for thousands of prisoners of war on both sides in World War II. The International Red Cross provided food, clothing, and medicines, while the Y.M.C.A. provided library supplies (largely books), athletic equipment, musical instruments, and chaplains' supplies. Both were major efforts and contributed immensely to the well-being of POWs. Volunteers from neutral countries, such as Switzerland and Sweden, with great dedication and at considerable personal risk, served Allied camps in Germany throughout the war.

Swedish lawyer Henry Söderberg, as the representative of the International Y.M.C.A., was responsible for the region of Germany in which Stalag Luft III was located. He visited the camp regularly and went to great efforts to procure and deliver items requested by the various compounds. As a result, each compound had a band and orchestra, a well-equipped library, and sports equipment to meet the different British and American national tastes. Chaplains also had the necessary religious items to enable them to hold regular services. In addition, many men were able to advance, and in a few cases, complete their formal education.

Söderberg remained in touch with many of his American friends by coming from Sweden to attend their reunions until his death in 1998. He kindly donated his rich collection of official reports, photograph albums, letters, and other materials documenting his work on behalf of the prisoners of many nations to the U.S. Air Force Academy Library. It is available to scholars, other researchers, and cadets alike.

The Great Escape of March 1944 triggered a tragically severe reaction from the Germans. The diversion from Germany's desperate war effort necessary to recapture the 76 men who got away through the escape tunnel reached Hitler's personal attention and he ordered 50 of the recaptured men to be shot. After this event, escape became more dangerous but attempts continued. In the confusion in Germany as the end of the war approached, especially after the Stalag Luft III Kriegies reached Moosburg, escape became easier and less dangerous. When it became obvious that the end was near, even the most ardent advocates of escaping decided to wait it out.

After the execution of 50 escapees during the Great Escape was known and the urns of their ashes were returned to the camp, the British POWs of North Compound built an impressive monument to their memory in the local Stalag Luft III cemetery. It remains to this day and the small cemetery is maintained by the local Polish people.

Nothing in Shakespeare could match the impact of the short speech delivered in the middle of the second act of "You Can't Take It With You" at the South Compound Theater on the night of January 27, 1945. Making an unscripted entrance, Col. Charles G. Goodrich, the senior American officer, strode center stage and announced, "The Goons have just given us 30 minutes to be at the front gate! Get your stuff together and line up!"

At his 4:30 staff meeting in Berlin that very afternoon, Adolf Hitler had issued the order to evacuate Stalag Luft III. He was fearful that the 11,000 Allied airmen in the camp would be liberated by the Russians. Hitler wanted to keep them as hostages. A spearhead of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev's Southern Army had already pierced to within 20 kilometers of the camp.

In the barracks following Colonel Goodrich's dramatic announcement, there was a frenzy of preparation -- of improvised packsacks being loaded with essentials, distribution of stashed food, and of putting on layers of clothing against the Silesian winter.

As the men lined up outside their blocks, snow covered the ground six inches deep and was still falling. Guards with sentinel dogs herded them through the main gate. Outside the wire, Kriegies waited and were counted, and waited again for two hours as the icy winds penetrated their multilayered clothes and froze stiff the shoes on their feet. Finally, the South Camp moved out about midnight.

Out front, the 2,000 men of the South Camp were pushed to their limits and beyond, to clear the road for the 8,000 behind them. Hour after hour, they plodded through the blackness of night, a blizzard swirling around them, winds driving near-zero temperatures.

At 2:00 a.m. on January 29, they stumbled into Muskau and found shelter on the floor of a tile factory. They stayed there for 30 hours before making the 15.5-mile march to Spremberg, where they were jammed into boxcars recently used for livestock. With 50 to 60 men in a car designed to hold 40, the only way one could sit was in a line with others, toboggan-fashion, or else half stood while the other half sat. It was a 3-day ordeal, locked in a moving cell becoming increasingly fetid with the stench of vomit and excrement. The only ventilation in the cars came from two small windows near the ceiling on opposite ends of the cars. The train lumbered through a frozen countryside and bombed-out cities.

Along the way, Colonel Goodrich passed the word authorizing escape attempts. In all, some 32 men felt in good enough condition to make the try. In 36 hours, all had been recaptured.

The boxcar doors were finally opened at Moosburg and the Kriegies from the South and Center Compounds were marched into Stalag VIIA.

Stalag VIIA was a disaster. It was a nest of small compounds separated by barbed wire fences enclosing old, dilapidated barracks crammed closely together. Reportedly, the camp had been built to hold 14,000 French prisoners. In the end, 130,000 POWs of all nationalities and ranks were confined in the area. In some compounds the barracks were empty shells with dirt floors. In others, barracks consisted of two wooden buildings abutting a masonry washroom with a few cold-water faucets. Wooden bunks were joined together into blocks of 12, a method of cramming 500 men into a building originally intended for an uncomfortable 200. All buildings were hopelessly infested with vermin. As spring came to Bavaria, some of the more enterprising Kriegies moved out of the barracks into tents that had been erected to accommodate the stream of newcomers still coming in from other evacuated stalags. Some men chose to sleep on the ground, setting up quarters in air raid slit trenches. The camp resembled a giant hobo village.

On the morning of April 29, 1945, elements of the 14th Armored Division of Patton's 3rd Army attacked the SS troops guarding Stalag VIIA. Prisoners scrambled for safety. Some hugged the ground or crawled into open concrete incinerators. Bullets flew seemingly haphazardly. Finally, the American task force broke through, and the first tank entered, taking the barbed wire fence with it. The prisoners went wild. They climbed on the tanks in such numbers as to almost smother them. Pandemonium reigned. They were free!

Two days later, General Patton arrived in his jeep, garbed in his usual uniform with four stars on everything including his ivory handled pistols. He was a sight to behold. The prisoners cheered and cheered. The Longest Mission was finally over!

The reality of liberation was a very emotional experience for the tens of thousands of men in POW camps throughout Germany. Many had had a dreadful experience in the last four months of the war as they were marched or transported as far as possible from advancing Allied forces. In the case of the thousands of former POWs at Moosburg, liberation also brought frustration and disappointment. Initially all support of the camp stopped. The Germans who ran the camp had all been taken off to prison camp and there was a serious delay before a U.S. Army support battalion was pulled out of the line to provide all necessary support for the camp. Next, the hundreds of French prisoners packed up and were flown out. General Charles de Gaulle had obtained first priority for their return from General Dwight Eisenhower. The Americans waited and, against the orders of their keepers, many quietly departed and hitched a ride to Paris. Eventually all American former POWs were moved out to nearby German airfields and transported by C-47 aircraft to the vast but now empty Combat Personnel Replacement Depots on the French Channel Coast.

The trauma, anxiety, hunger, and, even more importantly, the fellowship of the POW experience were not quickly forgotten. So the last fifty years have been filled with the joys of reunions, the nostalgic returns to the scenes of combat or the camps, the finding and thanking of those who gave assistance, and even friendly meetings with former foes. Some of these latter experiences have been very heart-warming.